Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference

| Site: | Pediatric Pandemic Network Learn |

| Course: | Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference |

| Book: | Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, January 29, 2026, 3:12 AM |

Table of contents

- 1. Preface

- 2. What is a Disaster?

- 3. Types of Disasters

- 4. The Impact of Disasters

- 5. The Disaster Cycle

- 6. Children in Disasters

- 7. Incident Command System (ICS)

- 8. Mass Casualty/Multi-Casualty Incidents (MCI)

- 9. The 4 S’s of Surge Capacity

- 10. Crisis Standards of Care

- 11. Triage

- 12. Ethics in Disasters

- 13. Decontamination

- 14. Preparedness

- 15. Hazard Vulnerability Analysis

- 16. Reunification

- 17. Telehealth

- 18. Afterward

Preface

We don’t often think about disasters until it is too late. As our world faces an increasing frequency of natural and human-made disasters, it is clear that the question has evolved from:

“What should I do if a disaster strikes?”

to

“What should I do when a disaster strikes?”

When I (Dennis) first tried to enter the world of disaster medicine, I was overwhelmed. There were so many concepts, terms, and an alphabet soup of acronyms. The resources were scattered. I found many overly “academic” and difficult to read. There’s got to be a better way to do this.

The Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference provides essential information for effectively dealing with any disaster. Our contributors aim to explore the vast trove of existing disaster medicine material and turn it into high-quality, concise, engaging, and pertinent summaries of what you need right now. The “chapters” are bite-sized and easy to digest with links to other resources should you want to learn more. Read and learn at your own pace.

Why We’re Different

This content is built with accessibility and clarity in mind. The plain, straightforward language supports readability and understanding, especially in high-stress scenarios.

Every topic is approached from a learner’s perspective. Unlike many expert-driven resources, this handbook is intentionally crafted for those who are just entering the field of disaster medicine.

Subject matter experts review all content for accuracy. Explanations are designed to bridge the gap between technical knowledge and practical understanding, avoiding assumptions and minimizing jargon.

Our Commitment to FOAMed

|

FOAMed stands for Free Open Access Medical Education. There are many great disaster medicine resources, texts, training programs and fellowships out there. But we strongly believe that disasters are a team sport. In order for everyone to play their part optimally, disaster medicine knowledge should be free and unrestricted to all who seek it. |

Get Involved

Our goal with this project is to create a community where we can learn from one another, share experiences and ideas, and engage in conversation. Our content is always changing and getting updated

Get in touch by engaging with our forum! Tell us what content is missing. Better yet, write a chapter for us! Or just tell us whether or not you’re enjoying the resource. We’d love to hear from you.

Access the Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference Forum.

Who We Are

|

|

Dennis Ren MDEditorDennis is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s National Hospital and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine at The George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences in Washington, D.C. He is a big proponent of Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAMed) and hosts a monthly critical appraisal podcast, “SGEM Peds” in collaboration with "The Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine" and “Ready. Prep. Go!” the podcast from the Pediatric Pandemic Network. He is passionate about exploring creative methods for science communication, knowledge dissemination, and knowledge translation. |

|

|

|

|

|

Brianna (Bri) Enriquez MDDisaster Subject Matter ExpertBri is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Seattle Children’s Hospital and Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, Washington. She also serves as the medical director for emergency management. |

|

|

|

|

|

Steven E. Krug MDSubject Matter ExpertSteve is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Ann & Robert H Lurie Children’s Hospital and Professor of Pediatrics at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois. He served as chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Disaster Preparedness Advisory Council and had also served on the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) National Biodefense Science Board. He has published extensively on the care of children in disasters in multiple journals. |

|

|

|

|

|

Shaileen McVeighSubject Matter ExpertShaileen’s passion for emergency medicine began early, inspired by her ER nurse mother and firefighter father. She has served as an EMT, 911 dispatcher, RN, and Pediatric Emergency Care Coordinator. Now a Hub site Manager for the PPN based at Yale School of Medicine, she draws on her diverse experience—as a responder, educator, nurse, and mother of four—to advance pediatric education and disaster preparedness. |

|

|

|

|

|

Allison EtcheverryContributorAllison is a medical student at The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences and a participant in the Disaster Medicine Scholarly Concentration. She is passionate about making health information easy to understand and accessible to those who need it. She has volunteered with and helped develop several community-based initiatives focused on health education and outreach. She is especially interested in translating complex topics into clear and actionable guidance for both patients and providers. |

|

|

|

|

|

Lauren OpenshawContributorLauren is a medical student at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Class of 2027 where she is a part of the Disaster Medicine Scholarly Concentration. Her clinical interests include pediatrics, disaster medicine, critical care, and emergency preparedness, particularly as they relate to protecting vulnerable children during natural disasters and public health crises. |

Produced By

|

Pediatric Pandemic NetworkThe Pediatric Pandemic Network is supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of cooperative agreements U1IMC43532 and U1IMC45814 with 0 percent financed with nongovernmental sources. The content presented here is that of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, visit HRSA.gov. |

Attribution-NonCommercial CC BY-NCThis license lets others remix, adapt, and build upon your work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge you and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms. |

What is a Disaster?

While this may seem like a simple question, organizations have different definitions.

|

|

United Nations Children’s Fund“A disaster is an occurrence disrupting the normal conditions of existence and causing a level of suffering that exceeds the capacity of adjustment of the affected community.” |

International Federation of Red Cross“Disasters are serious disruptions to the functioning of a community that exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources.” |

|

|

|

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction“A serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, leading to one or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts.” |

Bottom Line

The common theme that runs throughout all of these definitions is that a disaster is some kind of disruptive event that creates a scenario where needs overwhelm the existing resources or capacity.

The impact of an event may vary based on the type of disaster and who is affected. Preparation and planning are key.

Resources:

- UNICEF: C4D in Emergency Response

- International Federation of Red Cross: What is a disaster?

- UNDRR: Disaster

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 6/6/2025

Types of Disasters

Disasters disrupt lives, systems, and communities. Not all disasters look the same. They can arise from forces of nature or the actions of people. The causes may differ, but the outcomes often overlap: harm to individuals, strain on healthcare systems, and long-term recovery needs.

Disasters typically fall into two broad categories: 1. Natural and 2. Human-made.

Understanding the type of disaster helps guide planning, response, and recovery efforts.

Natural |

Human-Made |

|

|

|

Can you think of any disasters we didn’t list? Are they natural or human-made? |

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

The Impact of Disasters

Disasters have a ripple effect. There are typically immediate effects followed by long-term effects. Some disasters that may have effects that linger for years after the initial event have occurred.

Disasters can have both direct and indirect effects on the population and health care systems.

Direct Effects |

Indirect Effects |

|

|

|

Are there any other direct or indirect effects of disasters that you can think of? |

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

The Disaster Cycle

The Disaster Cycle is a model that helps communities and systems organize their efforts before, during, and after a disaster. Understanding each phase ensures that care is not only reactive but also proactive. This saves lives, preserves health systems, and builds resilience.

Phase |

Purpose |

Examples |

|

Response |

|

|

|

Recovery |

|

|

|

Mitigation |

|

|

|

Preparedness |

|

|

Disaster response isn't the responsibility of one person or organization. It’s a coordinated effort that depends on every aspect of the system working together. From clinical staff to logistics teams to community educators, everyone plays a vital role.

|

What role can you play in each phase of the disaster cycle? |

Resources:

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Children in Disasters

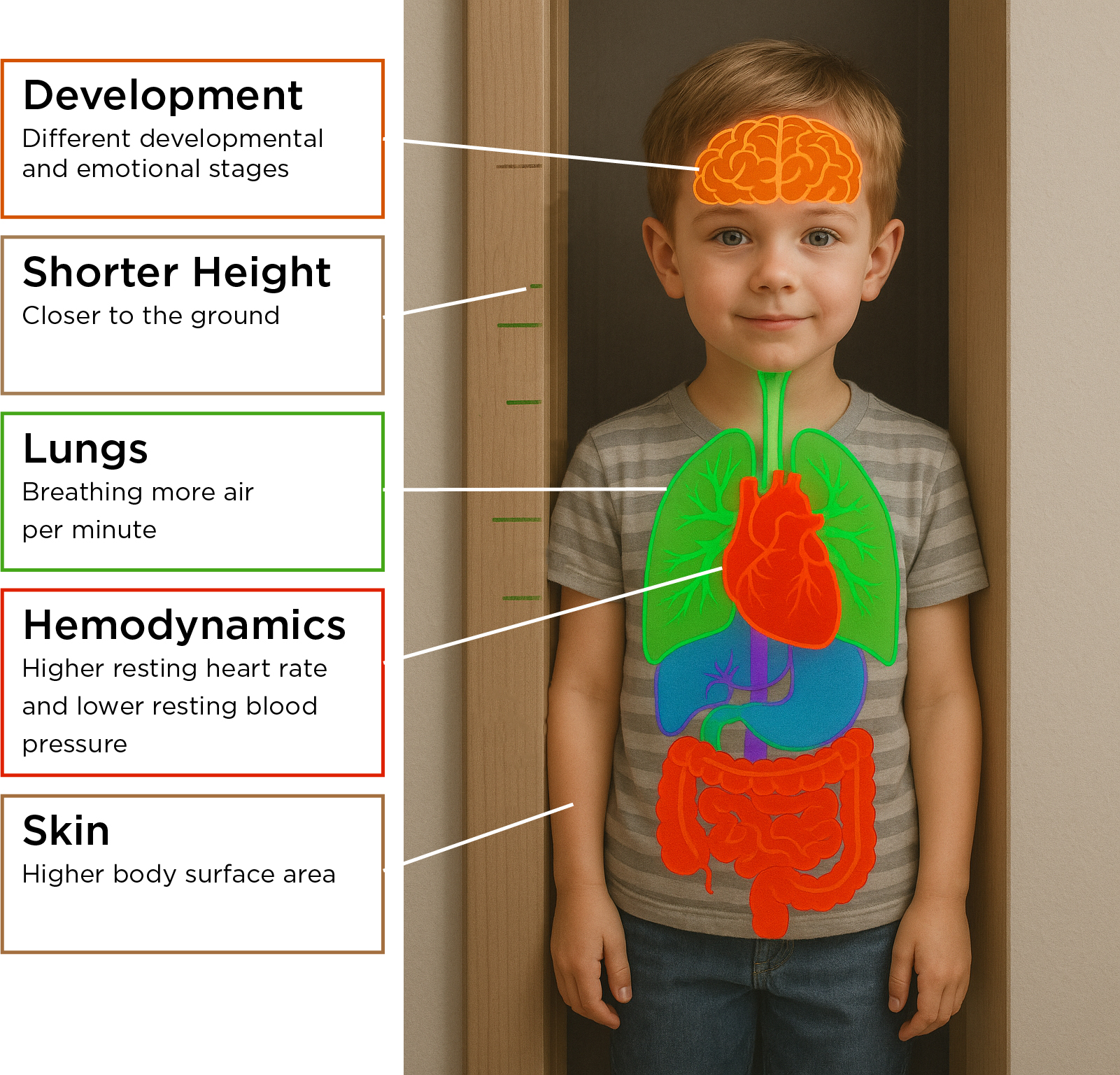

Children are not small adults. They have unique physical, emotional, and developmental characteristics that make them especially vulnerable during disasters. Unfortunately, they are often overlooked in preparedness planning, drills, and response efforts.

Let’s take a look at some of the things that make them unique.

Body Feature |

Why It Matters in a Disaster |

|

Breathe Faster |

Kids take in more air than adults so they can breathe in harmful gases more easily, especially ones that stay low to the ground. |

|

Shorter Height |

Being closer to the ground means they’re more exposed to harmful substances that sink low. |

|

More skin compared to body size |

Things that touch the skin (like chemicals) can affect them more. They can also get too cold more easily. |

|

Less blood |

Losing even a small amount of blood can be more dangerous for kids than for adults. It’s easier for kids to get dehydrated. |

|

Softer chest and belly muscles |

Their bodies don’t protect their lungs and organs as well. They can get hurt more easily from falls or hits to those areas. |

|

Bigger heads |

Their heads are heavier for their body size, which means they fall head-first more often and can get head injuries. |

|

Different Developmental/Psychosocial Stages |

This feature is pertinent to all aspects of disaster. Kids may be unable to walk or run away from danger. They may be scared of strangers, even those trying to help especially if they are dressed in lots of protective gear. They require short, simple instructions. It may take them longer to understand what they are being told. |

|

Can you think of any other considerations in caring for children during disasters? |

Why It Matters

Planning for disasters must intentionally account for pediatric needs from medical supplies for all ages and triage tags to psychological support and guidelines for reuniting families. Connect and partner with pediatric experts. Failing to plan for children means putting a significant portion of the population at greater risk during the very moments they are most dependent on adults.

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

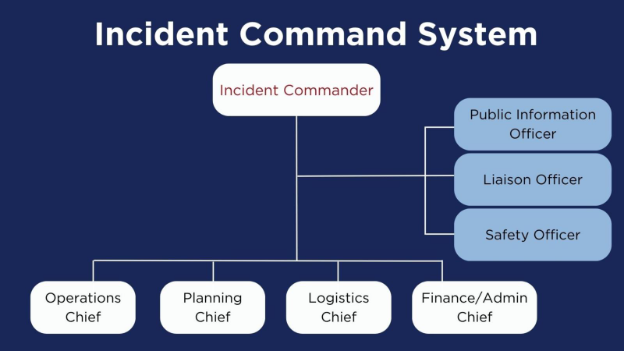

Incident Command System (ICS)

In a disaster, many groups may need to work together: fire departments, hospitals, government agencies, and more. Most disasters start at a local level. However, limited resources and personnel may require bringing in partners at the community, state, and federal levels. Coordinating multiple agencies in disasters can be challenging. It’s like having too many cooks in the kitchen. Who is in charge? How do we communicate effectively?

|

We learned a lot of difficult lessons after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Poor coordination led to delays, confusion, and miscommunication. |

A failure to address these potential issues may result in inefficiency, redundancy, and confusion in deploying resources and personnel.

The Incident Command System (ICS) is a flexible and scalable framework that can be used in any scale of disaster planning, response, and recovery.

5 Main Functions of ICS

- Incident Command

- Operations

- Planning

- Logistics

- Finance/Administration

Within Incident Command, additional staff can be added that includes a public information officer, liaison officer and safety officer.

|

Incident Command |

|

| Operations Section | Plans and performs activities towards accomplishing objectives |

| Planning Section | Collects, evaluates, and processes data about the situation and resources; disseminates this information |

| Logistics Section | Provides support that can include facilities, transportation, communication, supplies, food |

| Finance/Administration Section | Track, analyze, and estimate costs; identify cost-saving actions |

14 Main Features of ICS

| Common Terminology | Common terms around functions/functional units, resources, and facilities |

| Modular Organization | The structure expands based on the size, complexity, and hazards of the disaster |

| Management by Objectives |

Creates specific and measurable objectives Identifies actions and tasks that achieve those objectives Develops plans/procedures/protocols Tracks results |

| Incident Action Plan | Clear and concise communication of objectives that guides activities |

| Manageable Span of Control |

Ensure efficiency and effectiveness Management can communicate with and supervise all assets |

| Incident Facilities and Locations |

Key places include:

|

| Comprehensive Resource Management |

Tracks:

|

| Integrated Communication | A plan for how everyone communicates across agencies. |

| Establishment and Transfer of Command |

The command function should be clearly established at the beginning of an incident. The jurisdiction or organization with primary responsibility for the incident designates the Incident Commander and the process for transferring command. Transfer of command may occur during the course of an incident. When command is transferred, the process should include a briefing that captures all essential information for continuing safe and effective operations. |

| Unified Command |

Establishes jointly agreed upon objectives in situations where there are multiple overlapping authorities or jurisdictions involved. |

| Chain of Command/Unity of Command | Individuals report to one person. Note: it does not prevent informal communication and information sharing with other sections. |

| Accountability | Account for all response resources, including personnel, and adherence to all other ICS principles such as following the Incident Action Plan. |

| Deployment/Dispatch | Resource deployment when requested by authorities. |

| Information/Intelligence Management | Information gathered and shared through chain of command, including Essential Elements of Information (EEI). |

|

Has ICS ever be activated in your organization? What is your role and responsibility in the Incident Command System? |

Resources:

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 11/10/2025

Mass Casualty/Multi-Casualty Incidents (MCI)

A Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) or Multi-Casualty Incident is any event where the number of injured individuals overwhelms the usual emergency response capabilities of a community.

Because resources and capabilities vary across regions, EMS agencies and hospitals may define a MCI differently, and some may also classify MCIs by numbers.

For example:

-

A motor vehicle accident with five injured patients that occurs in an urban setting where there are multiple hospitals and EMS units may not add additional stress to the system.

-

The same motor vehicle accident with five injured patients that occurs in a rural setting with one EMS unit and one hospital could exceed available resources, making it an MCI.

Disasters are NOT just large MCIs

Although both events can cause a surge in demand, disasters are more severe than MCIs.

MCIs strain the system, but operations can often be adjusted to meet needs.

Disasters often go beyond stretching local resources. They overwhelm or break existing systems. Disasters may require outside assistance and coordinated response at local, state, or even federal levels.

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

The 4 S’s of Surge Capacity

Surge capacity refers to the ability to assess and care for a large increase in patients, which is often more than a healthcare system can handle during normal operations.

Managing a surge successfully depends on four critical components: Staff, Stuff, Structure, and Systems.

Staff

Having enough people during a disaster response is critical. Staffing includes more than just clinicians and nurses. Pharmacists, phlebotomists, laboratory technicians, respiratory therapists, environmental services personnel, and security staff all have roles to play during a surge.

Staff should be prepared to expand and be flexible in their roles. For example, many subspecialists and trainees provided care in the intensive care unit and hospital for COVID patients. Click here to read about Pandemic Preparedness: COVID-19 Lessons Learned in New York's Hospitals.

Having clear communication of who responds to a disaster and their specific roles is crucial - no matter where you work.

While it may seem like having a large number of people show up to help is a good thing, too many people can lead to unnecessary crowding and inefficiency. One way to manage and deploy staff is creating a disaster labor pool.

|

Does the place where you work have a process for calling in help in the event of a surge? |

Stuff

Supplies may be limited. This may be due to supply chain disruption or simply because the disaster has made it very difficult to get supplies to where you are working.

Examples from the COVID-19 pandemic include shortages of:

-

Personal protective equipment (PPE)

-

Ventilators and other medical equipment

-

Medications

-

Basic necessities like patient beds, linens, and food

Planning for supply needs ahead of time can help facilities respond more effectively when a surge hits.

|

What supplies does your facility need to continue operations? What does your supply chain look like? |

Structure/Space

Structure refers to the available facilities and spaces to provide care. To accommodate a large number of patients, it’s often necessary to be creative in space utilization. Some examples may include:

-

Converting private patient rooms to shared rooms and grouping patients with similar diseases

-

Establishing alternate care sites (e.g., gymnasiums, parking garages)

-

Converting existing areas to accommodate patient influx

-

Convert outpatient clinics to urgent cares/emergency departments

-

Operating rooms with ventilators become alternative intensive care rooms

|

Can you identify any space at your place of work that can serve as alternative areas for providing care? |

System

Set up a command center. Clear communication up and down the chain of command is critical for everyone to have a shared mental model. Use the Incident Command System to coordinate roles and decisions.

Build partnerships with community organizations, healthcare networks, and public health agencies. They may help share the load or provide vital resources.

|

What partnerships already exists for you? Can you identify other potential partners? |

Resources:

-

ASPR: Medical Surge Capacity and Capabilities (MSCC) Handbook

- Baker AH, Lee LK, Sard BE, Chung S. The 4 S's of Disaster Management Framework: A Case Study of the 2022 Pediatric Tripledemic Response in a Community Hospital. Annals of Emergency Medicine, Volume 83, Issue 6, 568 – 575. DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2024.01.020

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated:11/10/2025

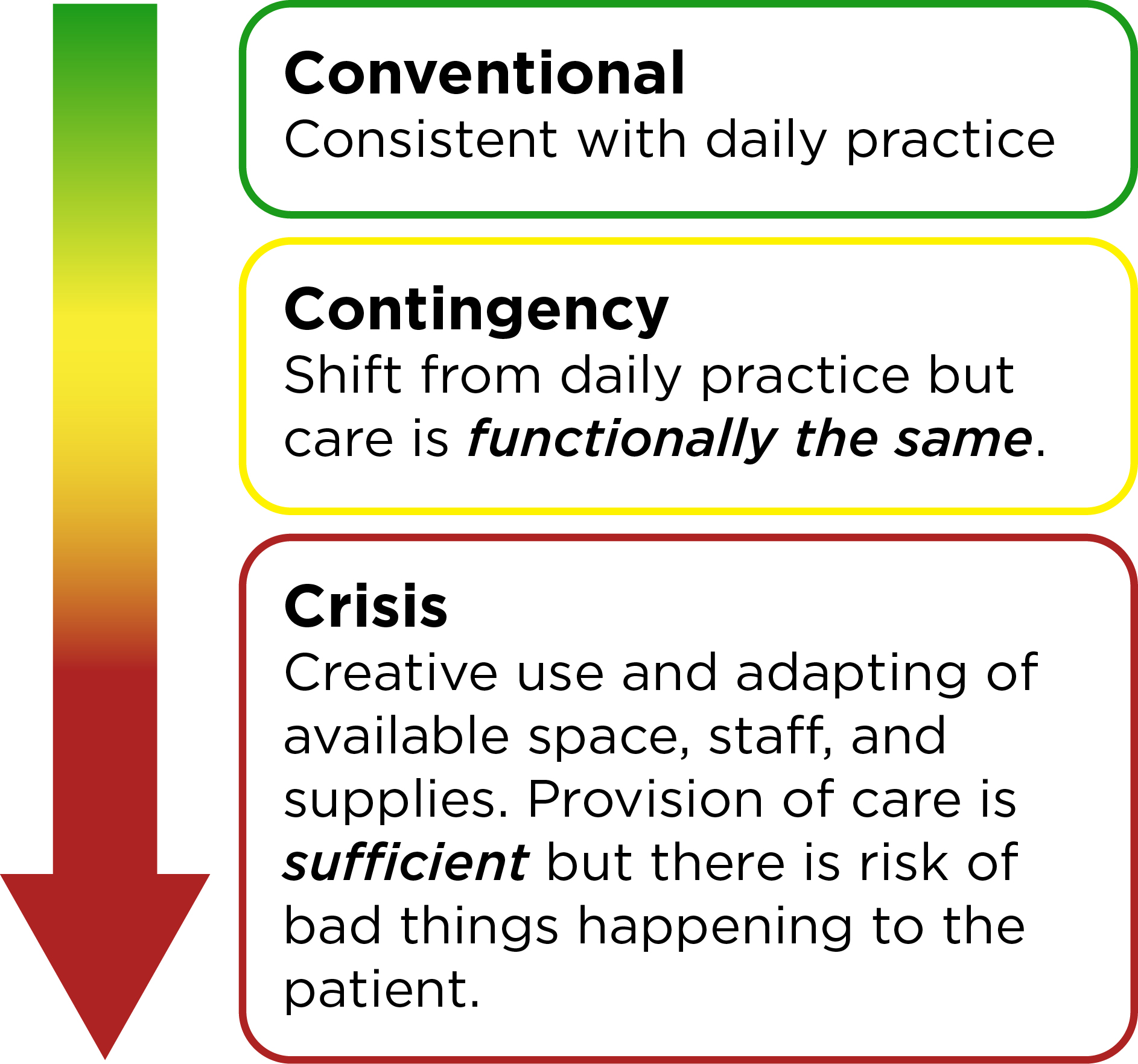

Crisis Standards of Care

In a disaster, hospitals and clinics may not have enough staff, space, or supplies to care for everyone in the usual way. When this happens, standards of care must change so that as many lives as possible can be saved.

Healthcare providers may have to adjust how care is delivered depending on the situation.

As care changes, providers must get creative with space, staff, and supplies. Some patients may face greater risks because the usual care can’t be given.

There are typically 3 phases:

Adapted from ASPR Tracie

Implementing crisis standards of care requires clear messaging to both healthcare staff and the community. This maintains transparency and sets expectations.

Even during a crisis, care should still be:

-

Fair: no one is treated differently based on things like age, race, or income

-

Consistent: patients with similar needs get similar care

-

Respectful and Ethical

Ethical and legal issues may arise when practicing at crisis standards of care. These issues can be magnified in the care of children.

As the situation improves, standards of care may gradually shift back towards the conventional.

|

How did the standards of care change in your area during the COVID-19 pandemic? |

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Triage

During disasters, triage decisions are made to determine who gets immediate care, who can wait, and (at times) who may not receive care at all. Triage requires rapid decision making based on very limited information.

|

Listen to this episode of Ready. Prep. Go! Podcast with Dr. Christina Hernon as she discusses the injuries she encountered and difficult decisions she had to make when she worked the medical tent on the day of the Boston marathon bombing. |

Triage comes from a French word meaning “to sort or separate out.”

Triage is dynamic and can happen in multiple settings including pre-hospital, emergency department, and hospital settings. The same patient may be triaged multiple times as their status may change over time.

The purpose of triage is:

Do the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

The goal of triage is:

Save the most lives.

Triage Systems

There are many triage systems that exist. Some triage systems are designed for children. The triage process is NOT perfect. There is no evidence that any particular triage system for children performs better than another.

Here are some of the most popular triage systems for pediatric patients in the United States:

It is important for you to be familiar with the triage system used in your local jurisdiction.

Components of Triage Systems

Although there are multiple triage systems, many triage systems include similar components:

- Rapid assessment of breathing, circulation, and mental status.

- Breathing: Are they breathing? Are they not? If they are breathing, how fast?

- Circulation: Is there a pulse or not? What is the capillary refill time?

- Mental status: Are they alert? Do they respond to voice or pain? Are they unresponsive (Often assessed using the AVPU system: Awake, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive)

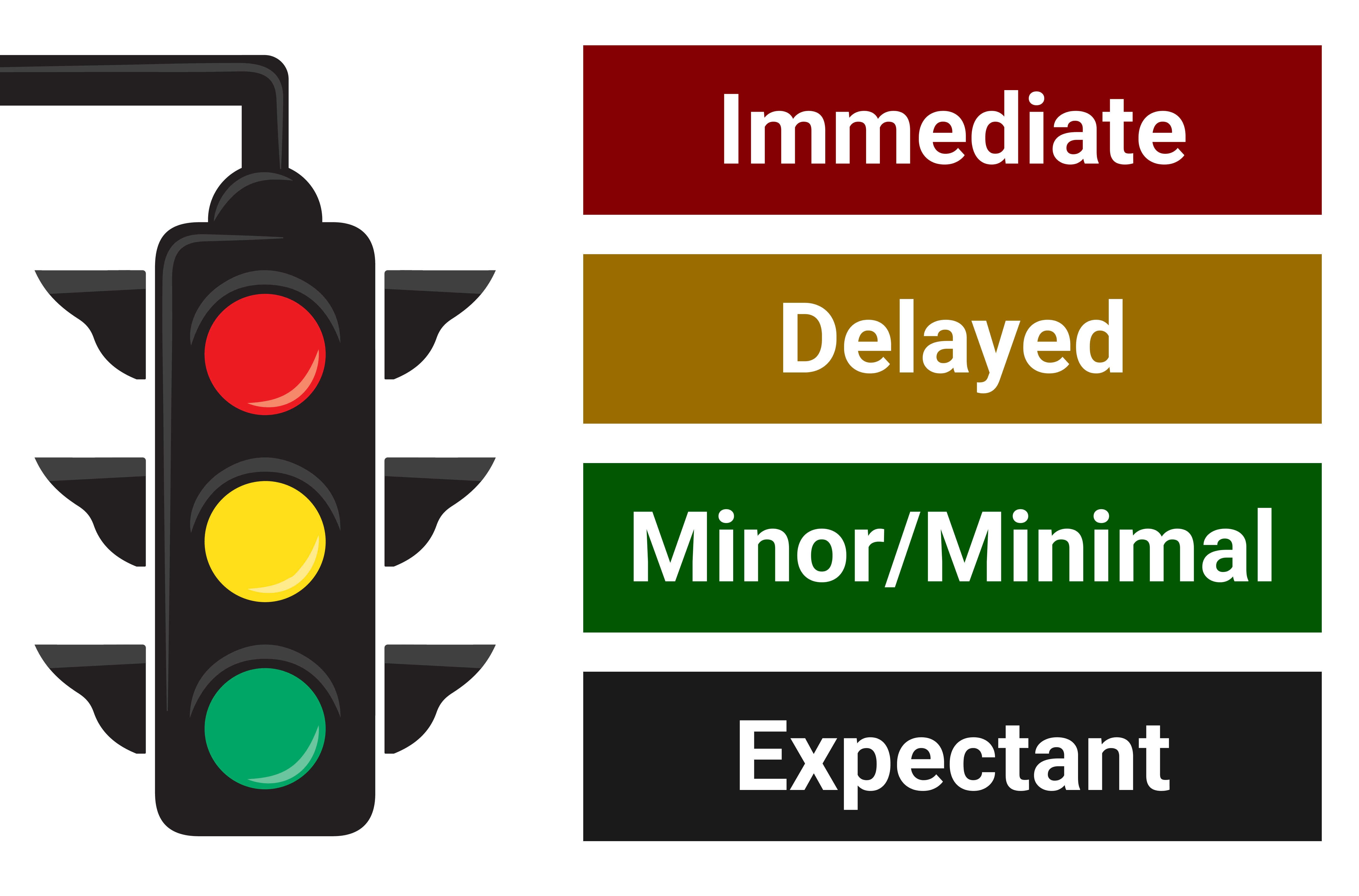

- Color-coded triage categories

Patients are triaged into categories to help determine how patients should be prioritized.

- Red (Immediate): Life-threatening injuries that need care right away to survive.

- Yellow (Delayed): Serious injuries, but treatment can safely wait a bit.

- Green (Minor/Minimal): Walking wounded with minor injuries; lowest priority for care.

- Grey/Black (Expectant): Injuries so severe that survival is unlikely given limited resources.

- Time-limited interventions

Simple, quick actions that can make a difference without using many resources:

-

Repositioning the airway.

-

Providing a few rescue breaths.

-

Decompression of the chest.

-

Application of tourniquet to control bleeding.

-

Administering an antidote via autoinjector.

Any intervention in triage should not require a large number of people or extensive time.

|

Triage decisions are hard to make. Take a moment to practice by checking out this case-based triage module. |

|

Check out this fast-paced, prehospital practice triage simulation. |

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Ethics in Disasters

Ethics

Ethics help us figure out what’s right and wrong. In disaster medicine, ethics can help guide us when we make hard choices and it’s not always clear what the “right” answer is.

There are four basic principles:

- Beneficence: Do good

- Non-Maleficence: Avoid harm

- Respect for Autonomy: Respect peoples’ choices:

- Justice: Be fair

Ethics and Disaster Settings

We often need to make tough decisions in all phases of a disaster. These decisions should try to balance the needs of individuals and the community, especially when resources are limited. We may not be able to save everyone. But with a plan, we can make decisions that are thoughtful, fair, and focused on doing the most good.

Pediatric Ethical Considerations

Children tend to be left out of disaster planning, and that is a problem. Children need special attention in disaster planning due to their unique considerations.

Ethically, we should include children in disaster plans. That means setting aside the right resources:

- Child-size equipment

- Pediatric medications

- Staff trained to care for kids

It also means planning for their mental health, which is often affected long after the event.The World Health Organization (WHO) and other relief organizations recommend psychological first aid as a first-line intervention in disaster settings.

Useful Resources:

- Download and review the Sphere Project

- Pediatrics in Disasters (PEDS), A Course of the Program Helping the Children

- How to Help the Children in Disasters

- Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers

- PPN Learn: Pediatric Behavioral Health in Disasters Curriculum

- PPN Learn: Disaster Medicine Curriculum Module 2

Before the Disaster

Doing the right thing starts with good planning and preparation. Preparation improves ethical decision-making and reduces conflicts during disaster responses.

Before the disaster hits:

- Review local laws and regulations.

- Create ethical guidelines and protocols.

- Set up an on-call ethics committee.

- Train staff to handle tough decisions.

Disaster Response Ethics Trainings:

Ethical training in disaster preparation helps prevent harm in the field, aids in decision-making / conflict resolution, and helps manage moral stress.

- Training should cover cultural contexts, teamwork, conflict resolution, and communication skills.

- Case studies are especially helpful because they allow responders to discuss and reflect on ethical issues in a practical context. They show how real decisions play out under pressure.

During the Disaster

Topic |

Considerations |

|

Resource Allocation |

During disasters, standards of care may change and resources can be scarce. We want to maximize benefits while conserving precious resources. Some strategies include:

|

|

Triage |

Triage helps us prioritize which patients need care first and who can be saved. Recommended Practices for Ethical Triage

Ethical Triage: What’s Fair?

Watch Out for Bias Bias can sneak in even when we try to be fair. Some groups (children, elderly, those with chronic illnesses, people in marginalized communities) may be unintentionally deprioritized. Know your community, plan ahead, and work to close these gaps. |

|

Informed Consent |

Things move fast in a disaster. There might not be time for full informed consent. Respect and transparency is important. Explain decisions as clearly as possible and get consent if possible. |

|

Individual vs. Community Rights |

Sometimes what’s best for the community may conflict with personal freedom. Quarantines, mandatory vaccinations, and lockdowns raise tough questions. Review and update these policies and recommendations often and to make sure they stay fair. |

|

Communication |

Clear, honest communication builds trust and reduces fear. Acknowledge when there is uncertainty. Be wary of misinformation or disinformation. Use social media responsibly. Some teams now train media staff in ethical reporting during disasters. |

After the Disaster Research

Disasters are opportunities to learn from mistakes and improve existing systems. Research must still follow ethical rules:

- Get community support

- Ensure participant and research team safety (physical and psychological)

- Get consent whenever possible

- Make sure research doesn’t get in the way of treatment

References

- Ciottone GR, ed. Ciottone’s Disaster Medicine. Third edition. Elsevier; 2023.

- Kathleen Geale S. The ethics of disaster management. Disaster prevention and management. 2012;21(4):445-462. doi:10.1108/09653561211256152

- Ozge Karadag C, Kerim Hakan A. Ethical dilemmas in disaster medicine. Iranian red crescent medical journal. 2012;14(10):602-612.

- Simm K. Ethical Decision-Making in Humanitarian Medicine: How Best to Prepare? Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2021;15(4):499-503. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.85

- Leider JP, DeBruin D, Reynolds N, Koch A, Seaberg J. Ethical Guidance for Disaster Response, Specifically Around Crisis Standards of Care: A Systematic Review. American journal of public health (1971). 2017;107(9):e1-e9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303882

- Antommaria AHM, Powell T, Miller JE, Christian MD. Ethical issues in pediatric emergency mass critical care. Pediatric critical care medicine. 2011;12(6 Suppl):S163-S168. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e318234a88b

- Reid C, Hillman C. Children in a disaster: health protection and intervention. BMJ Mil Health. 2022;168(6):473-477. doi:10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-002010

Written by Allison Etcheverry

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Decontamination

Decontamination: Removal of harmful substances from a patient’s body to prevent further absorption by the patient and transmission.

These agents can include:

- Chemical – e.g., industrial spills, nerve agents

- Biological – e.g., anthrax, viral exposure

- Radiological – e.g., radioactive dust or particles

Children may be exposed to these substances through accidental releases from chemical plants, transportation accidents, or intentional terrorist attacks.

Staff caring for patients should be trained to understand how to protect themselves in any incident that requires decontamination.

|

After a train derailment in Ohio, vinyl chloride was released into the community. In addition to immediate concerns about exposure to the harmful substance, there may also be longer term impacts to the surrounding community. |

The smaller the child, the greater the health risks.

Special Considerations

- Reduce the risk of hypothermia. When water is needed for decontamination, use warm water and temperature-controlled environments.

- Keep in mind that some victims may not be able to walk. It is important to have proper equipment such as rollers/conveyers, gurneys, wagons, etc. to help them through the decontamination process.

- Use pictograms to help children understand the steps of decontamination.

- Have instructions available in multiple languages.

- Provide child-friendly spaces and support to ease fear and anxiety, involve child-life or social work if able.

- Avoid separating children from caregivers unless absolutely necessary. If separation occurs, reunification plans must be in place and clearly communicated to the patient, if they're able to understand, and to their caregivers.

99% of chemical contamination can be eliminated by removing clothes and wiping skin with paper towel or dry wipe.

Source: Primary Response Incident Scene Management (PRISM)

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Preparedness

Preparedness: “a continuous cycle of planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluating, and taking corrective action in an effort to ensure effective coordination during incident response.”

Organizations, communities, households, and individuals should all be prepared for disasters.

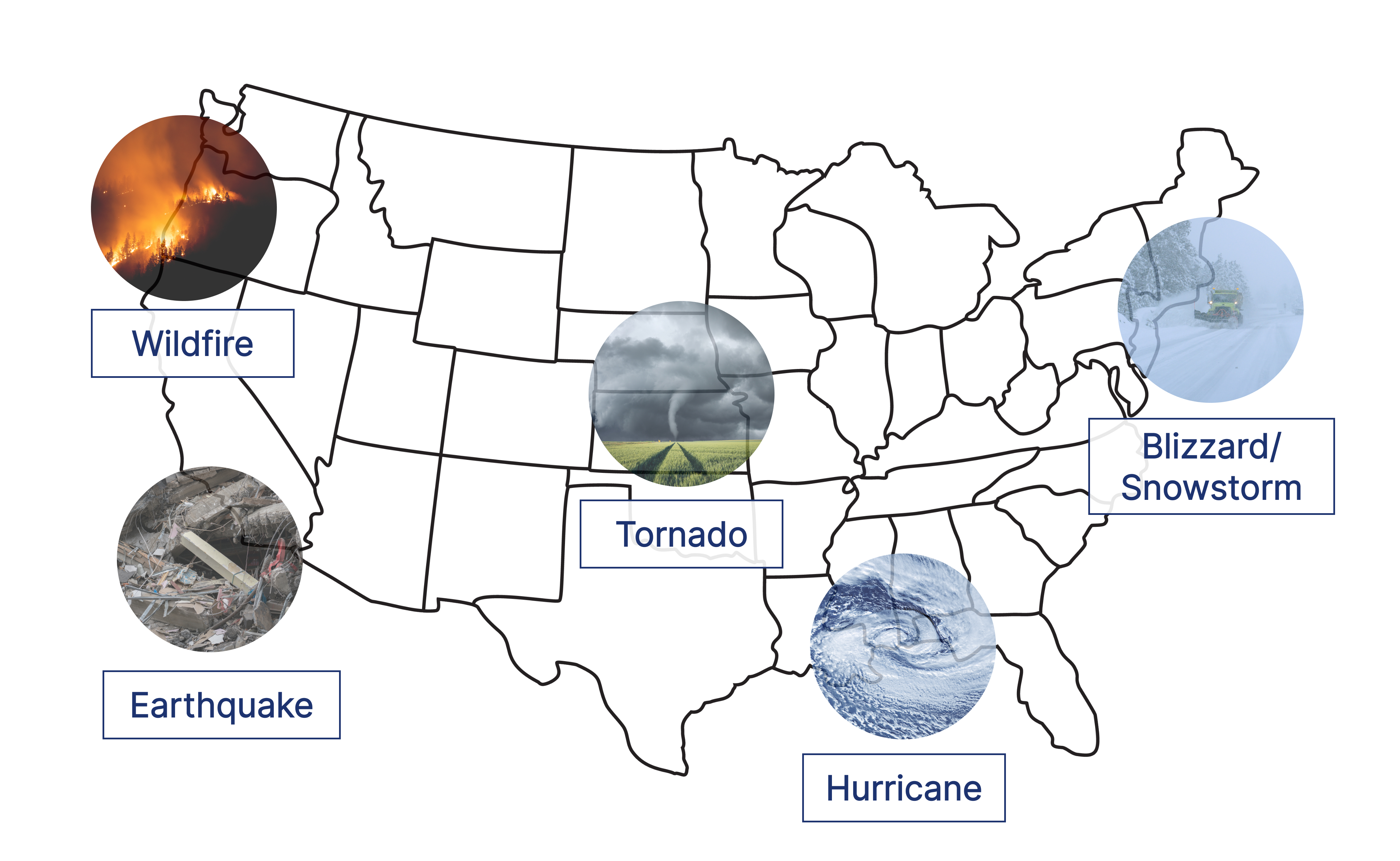

"But there are so many disasters? Where to begin?" It’s true that different disasters may pose different dangers, but you can still plan for them.

An “all hazard approach” means considering all potential threats and dangers. Evaluate how likely they are to happen. Prepare accordingly.

Here are some examples of disasters that may impact certain regions of the country.

No matter where you are, you should:

- Stay informed. Sign up for any early warning systems (EWS).

- Create emergency plans.

- Gather appropriate supplies in an emergency kit.

- Be prepared with enough supplies to last at least 72 hours.

- Practice and drill. Regularly review and practice emergency plans.

- Emergency kits should be checked and maintained every 6 months.

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Personal

Preparedness starts with YOU. As the saying goes, “To take care of others, start by taking care of yourself,” is most notably featured as the title of a Harvard Business Review article by Whitney Johnson and Amy Humble, published on April 28, 2020. Prepare a disaster kit that is ready to go if disaster strikes.

Most organizations recommend having enough water, food, and supplies to last at least 72 hours.

Signing up for any early warning system or emergency alert systems helps increase awareness of any approaching disasters.

Disaster kits can be kept at home, at work, and also in your car as disasters are unpredictable.

Here is a list of items to include in a basic disaster kit:

- Battery or hand-powered radio

- Cell phone with charger and extra battery

- Extra batteries

- Extra medical equipment for adults/CYSHCN

- First aid kit

- Flashlight

- Food (non-perishable)

- Food and water for animals

- Garbage bags

- Important documents (passports, bank records, insurance documents, etc.)

- Maps

- Multi-tool (with can opener)

- Over the counter medications

- Plastic sheets, duct tape, paracord

- Prescription medications

- Toilet paper and personal hygiene products

- Water (at least one gallon per person per day)

Disaster kits should be maintained and updated regularly (every 6 months).

While you may buy pre-made disaster or emergency kits, it may be more cost-effective and beneficial to create a personalized kit. Your kit can be customized to the most common threats that you may face.

Resources:

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Family

Family preparedness builds upon the concepts discussed in personal preparedness.

Include all family members - including children, elders, and pets - in creating and updating emergency preparedness plans.

Meeting Place

Establish a designated meeting place in case of evacuation or shelter-in-place scenarios.

- During evacuation, consider a meeting place in the neighborhood.

- During shelter in place, consider a meeting place in the home.

Communication

How will you communicate amongst the family?

Important phone numbers, emails, and other contact information should be easy to access.

Program important numbers into cellphones and have a designated contact for disaster situations. This is critical for younger children so they know who to call outside of disaster area if not able to contact immediate family.

Have a back-up plan in case a meeting place becomes inaccessible or forms of communication fail. For example, keep a list of phone numbers in a go bag in case cell phones are lost or out of power.

Involve everyone in practicing these plans!

Resources:

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Children

Depending on their age, children may require additional items in their disaster kit. Children can participate in disaster preparedness and planning. You can engage children in a scavenger hunt to help collect these items.

Infants

- Diapers and wipes

- Milk or formula

- Pacifier

- Thermos to keep things hot or cold

- Trash bag for soiled diapers

School-Age Children

- Paper and markers/crayons

- Snacks

- Stuffed animal or blanket for comfort

- Toy/Book/Game to keep them occupied

|

“The next time that you’re packing for a vacation and you’re gathering all your supplies, start to create your go bag.” Listen to this episode of Ready. Prep. Go! With Dr. Natasha Gill, pediatric emergency medicine physician and co-director of disaster management, as she describes how to assemble a disaster kit for you and your family. |

Resources:

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs

Children and youth with special healthcare needs (CYSHCN) represent a growing population.

These children require additional considerations in disaster planning due to physical, developmental, or behavioral differences.

For example, a child with vision or hearing impairment may need alternative methods to convey important information.

Possible solutions include:

- Assigning a person to help them

- Create a medical bracelet or laminated card with important medical information

Medications

CYSHCN may have various medications so it is important to include a supply of extra medication.

Some medications may need to be refrigerated.

Technology and Equipment

Some children may depend on technology and specialized medical equipment. These can include:

- Blood sugar monitoring tools

- Back-up power source or batteries for medical equipment

- Catheters

- Feeding pump

- Ice packs to keep medications cold

- Nebulizers

- Ostomy care supplies

- Pill cutters/crushers

- Syringes

- Supplemental oxygen

- Tracheostomy care supplies

- Ventilator (Bag valve mask or BVM, if without power)

Some children require special communication devices:

- Electronic tablets

- Picture boards

For equipment that requires electricity, it is important to have a backup power source, extra batteries, or charging cords for the equipment.

Transportation

CYSHCN may also need special equipment for transportation.

This can include

- Vehicles

- Wheelchairs

- Walkers

During evacuation, they may need access to slides or ramps.

Emergency Information Forms

As healthcare information is often not shared between health systems, it is important that critical medical information be communicated effectively. The American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Emergency Physicians have created a template Emergency Information Form for CYSHCN.

These forms should include:

- Patient’s name and birthdate

- Emergency contacts

- Primary and subspecialty care providers

- Diagnosis/problem list

- Medications

- Devices/Equipment

- Allergies

- Advanced Directives

|

Taking care of children and youth with special healthcare needs during disasters and everyday emergencies can pose unique challenges. Listen to these two episodes of Ready. Prep. Go! With Dawn Bailey and Kylie McElroy to hear their experiences caring for their own children with special healthcare needs. |

Resources:

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Hazard Vulnerability Analysis

It helps organizations understand what could go wrong and take steps to prepare before a disaster happens. A hazard vulnerability analysis (HVA) helps identify and prioritize the biggest threats to your workplace.

There are 4 main steps:

- Identify potential hazards: Think about all the types of events that could affect your workplace: natural disasters, cyberattacks, safety events (violence/shootings), utility failures, or chemical spills.

- Evaluate likelihood and potential impact: For each hazard, estimate how likely it is to happen and how serious the consequences would be if it did.

- Risk stratify hazards: Rank or group the hazards based on their overall level of risk (likelihood × impact). This helps focus attention on the most critical threats.

- Take steps to help prepare: Use risk rankings to create or update emergency plans, stock necessary supplies, and train staff appropriately.

HVA’s can be conducted in conjunction with community partners or those outside of your immediate institution. These outside perspectives not only help enhance discussion but can also lead to establishing crucial partnerships and identifying additional resources

Resources:

- To see a template of a HVA, review California Hospital Association resources.

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Reunification

Reunification: process of reuniting unaccompanied children with their families

Children may be separated from their caregiver during disasters. Children, caregivers, and family members may be brought to different hospitals, care sites, or even different states.

|

This problem became magnified during Hurricane Katrina when over 5,000 children were separated from their families. It took over 6 months for them to be reunited. Click here to read a related news article. |

Separated children not only suffer emotional trauma, but are also at higher risk for abuse, neglect, and abduction.

Who should have reunification plans?

Families should have a clear communication plan during disasters and emergencies that includes important contact information and possibly a pre-agreed upon reunification site.

If the child is able, they should know the name of trusted adults, contact information, email addresses, and phone numbers. Caregivers can teach children their primary caregivers’ first and last names and address as early as possible.

Hospitals should engage key stakeholders (including child life specialists, social workers, and chaplains) to develop reunification plans in case of disasters. Plans should include documentation, caregiver verification, and psychological support for separated children.

Child-care centers, and schools should also be responsible for creating written reunification protocols and practicing reunification drills regularly.

Here is a family reunification plan template.

All reunification plans should be practiced and drilled.

Identification

Children do not typically carry any form of identification.

Depending on age, infants/toddlers sometimes cannot self-identify.

There are a few methods of helping identify unaccompanied children but no system is perfect.

Registries

There are various registries for unaccompanied/missing children that include:

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children

- Unaccompanied Minors Registry

- American Red Cross: Contact Loved Ones

Information is often not shared among registries. National registries are often unavailable for local emergencies.

Image-based Identification

Although pictures may be a helpful aid in reuniting children with families, caregivers have shared that under stressful circumstances it was difficult for them to identify their children by this method alone.

These systems can also include the ability to search for the child based on details such as skin color, eye color, age.

A limitation of image-based identification is if the child suffered a severe and disfiguring trauma or injury, they may be difficult to recognize.

DNA-based Identification

This method has been used by federal agencies to help reunite children from migrant families with parents. This technology is not readily available everywhere. It also becomes limited in cases where caregiver and child are not biologically-related (for example, adoption).

There is not one perfect strategy or method for identifying children who are separated. Each approach has limitations.

Privacy Concerns

There is debate over who parents and caregivers trust with information about their child that is uploaded onto registries or databases.

Agencies should be mindful of any potential violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in their reunification planning.

Written by Dennis Ren

Last updated: 11/10/2025

Telehealth

Telehealth is the use of technology to deliver medical care from a distance. It helps connect patients and healthcare providers.

Telehealth can be especially helpful during periods of limited healthcare availability such as pandemics or global disasters.

|

There are many types of telehealth:

|

|

The first use of telehealth dates back to the early 1900s. One of the first published examples is the use of a telecardiogram by Dr. Einthoven.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine was not widely used in the US healthcare system. There were many barriers:

- Limited insurance coverage.

- Strict state licensing rules.

- Concerns over patient privacy.

That changed quickly as COVID-19 spread. New policies expanded what was allowed. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact allowed doctors to obtain licensure in multiple states, allowing them to see patients across state lines. The compact was introduced in 2017 and currently includes 37 states in addition to the District of Columbia. Insurance started covering more telehealth visits. Even apps like Zoom, Skype, and FaceTime became acceptable for care.

During the first three months of the pandemic, telemedicine encounters increased more than 700%! (Figure 1). Providers used live video to assess and monitor patients in their own homes to determine who needed to seek care in the emergency department or be hospitalized.

Today, telemedicine continues in US healthcare delivery, which allows patients to connect with primary care services and subspeciality care and allowing providers to communicate with one another.

The role of telehealth in caring for children in disasters

Telehealth can play a key role in helping children affected by disasters. It allows providers to reach children in areas with few resources or limited access to specialists.

Telehealth can be used to:

- Triage and treat children affected by disasters.

- Coordinate care and follow up with subspecialists.

- Provide mental health support.

- Connect patients and providers who are geographically separated or inaccessible to each other.

The use of telehealth between providers allows complex care coordination for a child who may need multi-specialty input.

What are the barriers?

Telehealth has big potential, but there are still many challenges.

- Cost: Not everyone has the money for equipment or platforms to establish telehealth practices.

- Access to technology: Patients and families may not have reliable access to smart phones, computers, or other devices to access telehealth services.

- Technological literacy: Not everyone may know how to use new technology platforms. Pre-recorded how-to videos may help them understand how to use the telehealth program.

- Technology glitches: There may be issues with internet access or the telehealth platform itself. Have a back up plan. Consider providing IT phone numbers or links for patients to call if software is not running properly or plan to use another device.

- Data privacy: Certain telehealth platforms may not have appropriate security to protect private healthcare data.

- Provider liability: Provider should ensure their malpractice insurance covers telehealth or may purchase this additional coverage.

Here is a list of possible telehealth platforms:

Platform |

Device Compatibility |

|

Audio phone call |

|

|

Apple Facetime |

|

|

Microsoft Teams |

|

|

Zoom |

|

|

Facebook Messenger Video Chat |

|

|

Doxy me |

|

|

Doximity |

|

Resources:

Patient:

Providers:

- Telehealth for providers (HHS.gov)

- Resource for Health Care Providers on Educating Patients about Privacy and Security Risks to Protected Health Information | HHS.gov

- CARES Act: AMA COVID-19 pandemic telehealth fact sheet | American Medical Association

- Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet | CMS

References:

-

American Medical Association. CARES Act: AMA COVID-19 pandemic telehealth fact sheet. American Medical Association. Published April 27, 2020.

-

Chiu M, Goodman L, Palacios CH, Dingeldein M. Children in disasters. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2022;31(5):151219. doi:10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2022.151219

-

Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet. CMS.gov. Published March 17, 2020.

-

Office for Civil Rights (OCR). HIPAA and Telehealth. HHS.gov. Published June 21, 2022.

-

Shaver J. The State of Telehealth Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim Care. 2022;49(4):517-530. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2022.04.002

-

Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, et al. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(5):573-590. doi:10.1089/tmj.2006.0073

Written by Lauren Openshaw

Last updated: 5/30/2025

Afterward - Help Us Grow This Resource

The Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference is designed to be a living, evolving resource, built for the community, by the community. As our knowledge grows and new challenges emerge, so will this guide. We encourage you to check back regularly for updates, new tools, and expanded content.

Your voice matters. Whether you have suggestions, corrections, success stories, or questions, we want to hear it all. We're especially interested in real-world insights that can help others better prepare, respond, and recover.

If you’d like to contribute to future editions or just share your feedback (good or bad), please write a post in the forum. Together, we can make this handbook stronger for everyone who cares for children in emergencies.

Access the Disaster Medicine Handbook: A Quick Reference forum.